Antony of the Desert

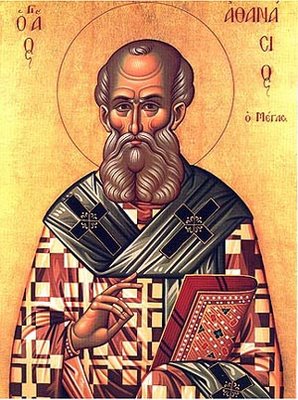

We had a couple of weeks last year during which we talked about demons quite a bit, for some reason. So I read Athanasius' hagiography of Saint Antony of the Desert.

Enjoy these ancient sources on Antony and the demons.

Other folks writing about Antony today:

Coming to the Quiet: Antony Yet Again

Mike Aquilina: Tomb with a View

John Paul: Antony of Egypt

S. Antony

S. AntonyBut those of his acquaintances who came, since [Antony] did not permit them to enter [his cell], often used to spend days and nights outside, and heard as it were crowds within clamouring, dinning, sending forth piteous voices and crying, 'Go from what is ours. What dost thou even in the desert? Thou canst not abide our attack.'The Life of Antony, ch. 13, +Athanasius of Alexandria. Written c. 356-362.

So at first those outside though there were some men fighting with him, and that they had entered by ladders; but when stooping down they saw through a hole there was nobody, they were afraid, accounting them to be demons, and they called on Antony. Them he quickly heard, though he had not given a thought to the demons, and coming to the door he besought them to depart and not to be afraid, 'for thus,' said he, 'the demons make their seeming onslaughts againt those who are cowardly. Sign yourselves therefore with the cross, and depart boldly, and let them make sport for themselves.' So they departed fortified with the sign of the Cross."

...Whereas formerly demons used to deceive men's fancy, occupying springs or rivers, trees or stones, and thus imposed upon the simple by their juggleries; now after the divine visitation of the Word, their deception has ceased. For by the Sign of the Cross, though a man but use it, he drives out their deceits.On the Incarnation of the Word 47.2, +Athanasius

Some Jews who went around driving out evil spirits tried to invoke the name of the Lord Jesus over those who were demon-possessed. They would say, "In the name of Jesus, whom Paul preaches, I command you to come out." Seven sons of Sceva, a Jewish chief priest, were doing this. (One day) the evil spirit answered them, "Jesus I know, and I know about Paul, but who are you?" Then the man who had the evil spirit jumped on them and overpowered them all. He gave them such a beating that they ran out of the house naked and bleeding.- The Acts of the Apostles, 19.13-16.